Ayo Walker

(dance)

Black Pruitt

(anti/interdisciplinary performing arts)

Cassandre Charles

(dance, mixed media, film)

Clara Auguste Mohagen

(dance)

Danza Orgánica

(dance theater)

Kera Washington

(music)

María Servellón

(film, video installation, video projection, video performance)

Yaraní del Valle Piñero

(dance, music and theater performance)

Zahra A. Belyea / Alia Croley

(spoken word and dance/movement)

Guest Artist: Isaura Oliveira

(dance theater)

Innovative puppetry brings Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison’s coming of age novel into a contemporary context. Pecola is a black girl caught in tragic circumstances. Her best friend narrates her search for the source of responsibility and for an understanding of her own part in the story. The production interrogates how identity is shaped, using a synthesis of puppets, puppeteers and actors. Celebrated South African artist Janni Younge’s puppetry highlights the formation and fragility of self, literally building the self as it is held and supported (or not supported) by a community at large.

With special support from the Paul M. Angell Foundation, Cheryl Lynn Bruce & Kerry James Marshall, Kristy & Brandon Moran. Co-produced by UC Davis & Janni Younge Productions.

Produced by special arrangement with THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY of Woodstock, Illinois

https://chicagopuppetfest.org/event/margaret-laurena-kemp-janni-younge/

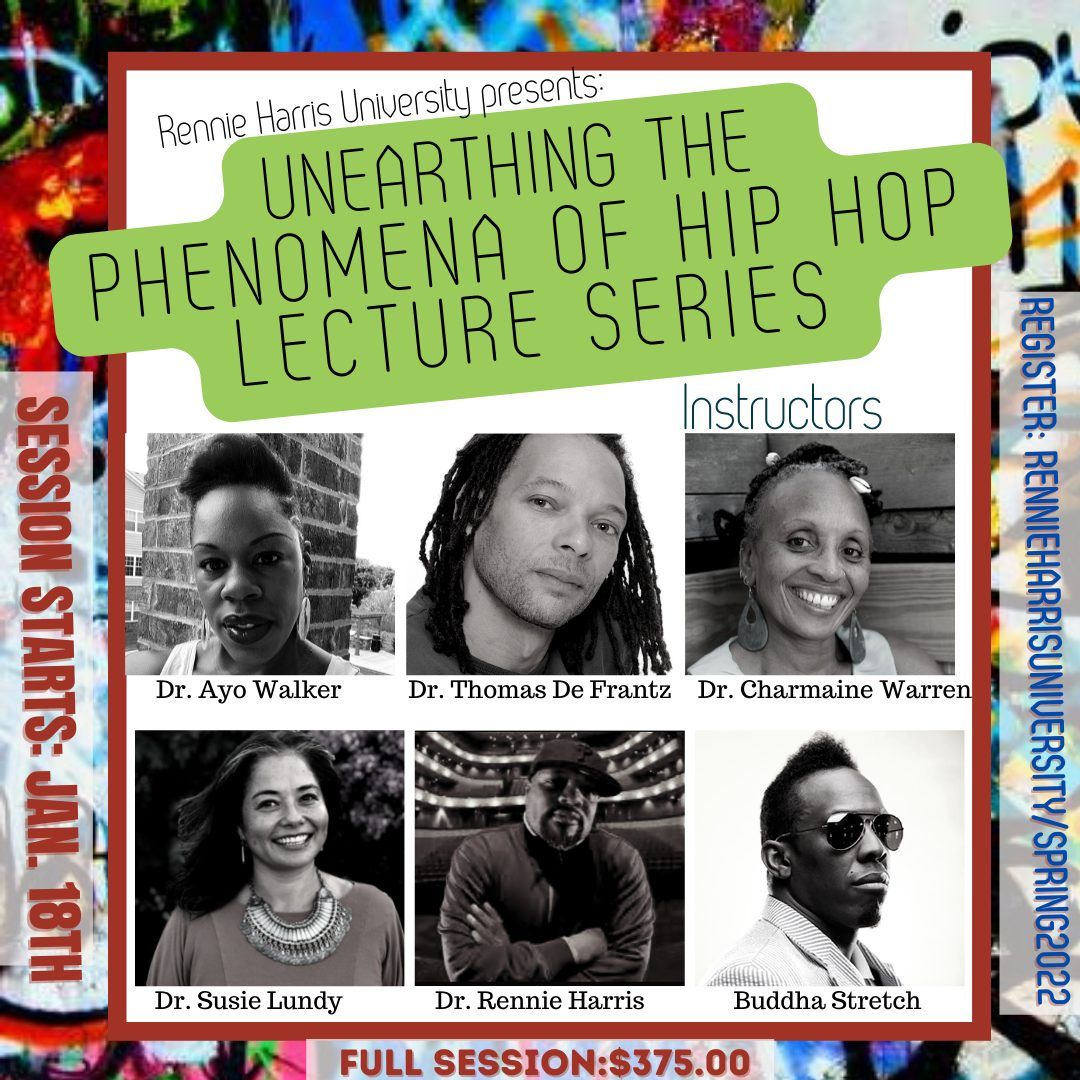

Instructor: Dr. Ayo Walker

Dates: March 17th-April 7th

Times: Thursdays 7-pm-8pm CST

Individual Session $75

The Black dancing body in Western societies have been historically oppressed by white/Eurocentric aesthetic ideologies that sought to correct and sanitize the culturally-othered-marked dancing body by way of ethnocentric and monocultural indoctrination. Decolonizing the Black dancing body in this course acts as a method of deprogramming monocultural and ethnocentric indoctrination while decoding and de(cipher)ing bodily oppression. Understanding how bodily autonomy vs bodily indoctrination affects dancers’ embodied cognitive development will become the essence for freeing the student’s groove (the default movement style of your body’s rhythmic interpretation) and personalizing their movement identity. The dancing body should not be expected to apply the same movement principles and qualities across all dance forms. Through online cipher sessions this course will engage with movement principles and qualities that invite students to explore movement possibilities beyond those indoctrinated in their bodies. In the cipher is where the dancer will discover their FREEDOM.

Dr. Ayo Walker is in her first year at APSU. In that short time she has become a leading voice on anti-racism and racial honesty and accountability on campus. In addition, her level of professional work and output has been above and beyond. In the world of theatre and dance, COVID-19 has been a difficult time to find opportunities for research and performance, but Dr. Walker has created opportunities and continued her stellar academic work.

In her first semester, Dr. Walker has set previous choreography on students, set new choreography on students, is planning on using those students as dance captains at a professional company where her work is being staged, had an article published in the Journal of Dance Education – the leading educational dance publication in the country ("Traditional White Spaces: Why All Inclusive Representation Matters") –, served as a manuscript reviewer ("Jazz Dance and African Roots"), and has been commissioned to write two chapters for an upcoming dance textbook ("Milestones in Dance History"). In addition, Dr. Walker has revamped the way Dance History is being taught at APSU, focusing on traditional dance spaces, their exclusion and "othering" of non-white innovators, and teaching the class in a non-linear format. This has changed the students approach to dance history and taught them important critical thinking skills, allowing them to investigate history through a wider lens and to make their own decisions based on research.

Since her arrival, Dr. Walker has modeled what it means to seek equity and inclusion. She understands and practices the need for her new generative pedagogical praxis that she calls “Entercultural Engaged Pedagogy,” which specifically involves a theoretical discourse in dance via the study of “othered” and marginalized dance histories. Acting as historical intervention in dance studies, she seeks to rectify the cultural racism often repressing higher education dance curricula. In addition, she has modeled academic excellence to her Intro classes. Arts intro classes are often treated as "easy A's" by students. However, Dr. Walker has introduced the idea of respect and academic rigor into her "Intro to Dance" class that requires students to treat the subject of dance with respect, academic integrity and honesty.

You can watch some of Dr. Walker's work in the next few months as the Spring Virtual Faculty Dance Concert will be streaming on the APSU Theatre & Dance Website: theatredance.apsu.edu. You can read her article, "Traditional White Spaces: Why All Inclusive Representation Matters," at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15290824.2020.1795179. Finally, her new work will be presented from May 20-22 at the Southern Theatre in Minneapolis, Minnesota. More information is available at https://rhythmicallyspeakingdance.org/the-cohort/.

We salute you Dr. Walker for your creativity, passion and rigor you bring to the classroom and the Arts.

- APSU African American Employee Council

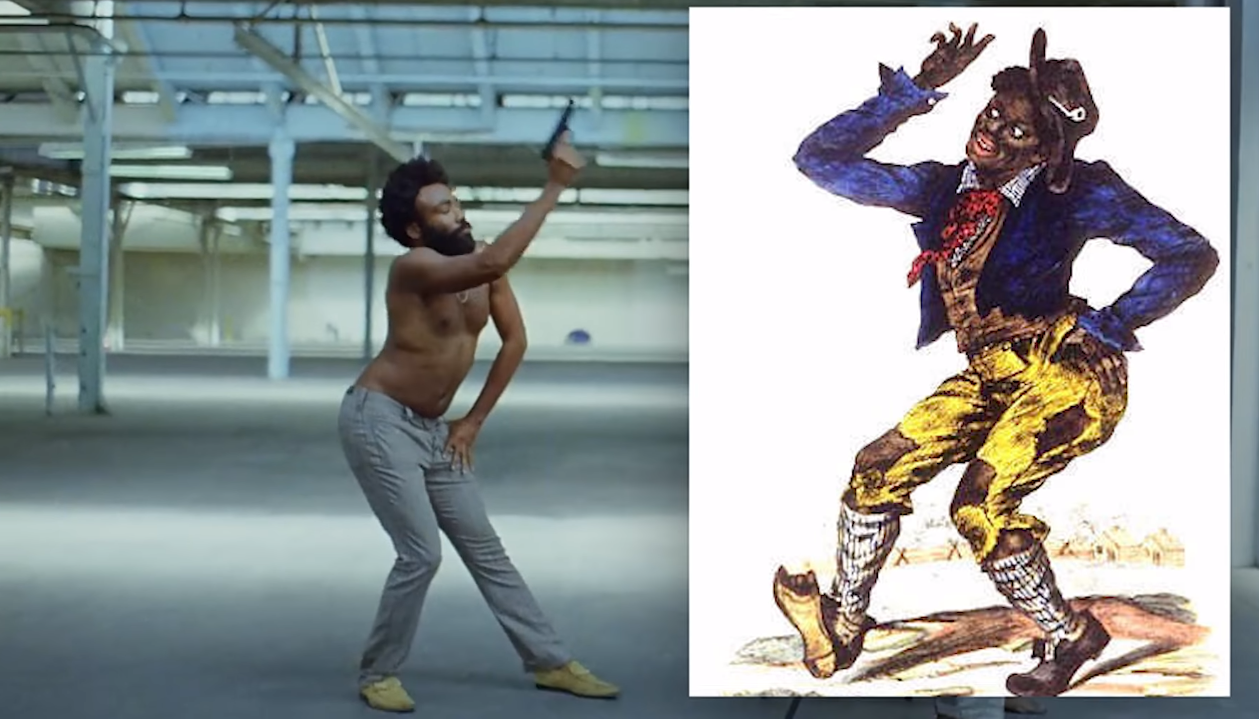

Whether or not we like it or agree with it, this particular performance of Blackness is arguably a new subgenre of hip hop music. “Decades after Zip Coon and Sambo shuffled, jived, and bug-eyed on the minstrel stage, hip-hop has once again made black face caricature a popular mode of American entertainment. Spinning car rims, ‘pimps and hoes,’ and ‘bling-bling’ jewelry have replaced the chicken and watermelon...” argues Travis L. Gosa. This subgenre of hip hop music fuels the momentum of tanning America, which I’ve interpreted as all-inclusive branding and marketing for the polyethnic consumer base it serves. Consider for a moment the urgency of all-inclusivity particularly when it seemingly excludes whiteness and its simultaneous snail’s pace towards equitable representation. I argue that all-inclusivity for the purposes of circumventing the decentering of whiteness is one reason for some performances of Hip Hop shifting from celebration to entertainment, which inadvertently contributed to the appropriation of a cultural movement now reduced to a minstrel show. Dr. Halifu Osumare states, “there’s a thin line between appropriation and celebration. Because while we were celebrating, they were appropriating.” Still, white’s cultural appropriation of black performances of celebration afforded us some agency when reproducing our images from the perspectives of the white gaze. For their entertainment, and our access to some agency and financial upward mobility, our self-exploitation and subsequent commodification became our way of achieving a piece of the “American Dream”. This reality complicates both 19th -20th century minstrelsy representations and 21st century re-presentations of minstrelsy. While a painful echo emanates from the legacy of Black minstrelsy, it also resonates, at its core a historic innovation and a means of resistance to the misrepresentations of Black culture by whites.

Hip hop artists who are embracing black progress by any means necessary are “changing what it means to be black and middle class in ways that make our proponents of traditional values cringe because they refuse to be disciplined into puritan characterizations of normative middle-class behavior” argues Davarian Baldwin. While minstrel-like elements in Hip Hop may be evident, I believe generalizing 21st century hip-hop rap as the latest form of minstrelsy is a risky supposition simply because it doesn’t represent, nor does it re-present a singular model. According to my investigation of the manifestation of Hip Hop’s rap music of the 21st century, the genre as a whole is being held accountable for portraying modern day blackface minstrelsy. While my research reveals that many Hip Hop artists are the targets of ridicule for performing as contemporary coons, rap music in general is suffering from the accusation of “buffoonery.” I argue that if today’s image of rap music is going to be labeled as a minstrel show, the history of the genre needs reevaluation, and a deeper investigation of its performative roots is crucial. There are various aspects of historical blackface minstrelsy and it is important to know what aspect of these performative utterances you are dealing with in order appropriately to label them. My sources (Austen and Taylor, 2012; Johnson, 2012; Lhamon, 2000; Lott, 1993) reveal that the performance choices and actions of minstrel artists were often purely practical in the process of accessing agency in the entertainment industry of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Sometimes those choices consisted of a method for negating the caricature depictions of Blacks and liberating the culture by creating performative counter-narratives. It could also serve as a medium for presenting parody, satire, and fiction via a “double-consciousness” approach. Still, Brenda Dixon-Gottschild argues that while “Minstrelsy was good in providing legitimate, paid work for black performers and preserving black plantation forms that might have otherwise disappeared, it was bad in etching a dire stereotype.”

My initial research question was: When being personally subjected to Hip Hop performance in a Black minstrel-like manner that may potentially garner financial gain and recognition, how should rap artists negotiate their performance choices? Now I ask, is there a non-stereotypical performance mode for repurposing the historical caricaturing of blacks for sport and profit by white men?

In Raising Cain Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop W.T. Lhamon (2000) notes, “the blackface figure always resisted, or did not easily fit into other peoples’ forms-and so gradually forced a form that gave it room of its own” (p.59). Then is this new subgenre of hip hop music a forced form that has established a space of its own, or will it always be under the weight of Blaxploitation?

The struggle with changing the joke and slipping the yoke is that the true self has been so distorted by, “the images produced by and for whites to justify Blacks’ oppression…that black people are trying to stay true to imagined identities that they’ve accepted and internalized and even reproduced… It’s startling that today, more than eighty-five years later, we are dealing with the same shadow…” says M. K. Asante Jr. in It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation.

What about the black caricaturing and minstrel-like performances by white rappers, such as Iggy Azalea, Tekashi 69, and Post Malone? Even if black rappers ceased their minstrel-like performances, would the representations of black minstrelsy in rap die in the 21st century where is was birthed or as Travis L. Gosa predicts, will we be “stuck lamenting the blackface tradition in the twenty-second century due to a lack of pragmatic advice” and or due to “this fantasy about the disposability of black life [which] is a constant in American history” as Teju Cole states. So, I’m concerned that like Gosa suggests, since “mainstream radio and music channels are saturated with dumbed-down rap lyrics and thug buffoonery, while political acts remain marginalized in the underground,” conscious rap may not prevail because it won’t be produced at the rate minstrelsy rap will, and even if we dead our own subversive caricatures will they finally be extinct?